Flat Earth

The Flat Earth model is a view that the Earth's shape is a flat plane or disk. Most pre-modern cultures have had conceptions of a flat Earth, including ancient Greece until the classical period, the Bronze Age and Iron Age civilizations of the Ancient Near East until the Hellenistic period, Ancient India until the Gupta period (early centuries AD) and China until the 17th century. It was also typically held in the cultures of the New World until the time of European contact, and a flat earth domed by the firmament in the shape of an inverted bowl is common in pre-scientific societies.[1]

The paradigm of a spherical earth was developed in ancient Greek astronomy, beginning with Pythagoras (6th century BC), although most Pre-Socratics retained the flat earth model. Aristotle accepted the spherical shape of the earth on empirical grounds around 330 BC, and knowledge of the spherical earth gradually began to spread beyond the Hellenistic world from then on.[2][3][4][5]

The misconception that educated people at the time of Columbus believed in a flat earth has been referred to as "The Myth of the Flat Earth".[6] In 1945, it was listed by the Historical Association (of Britain) as the second of 20 in a pamphlet on common errors in history.[7]

Contents |

Historical development

Ancient Near East

Belief in a flat Earth is found in mankind's oldest writings, such as the Epic of Gilgamesh. In early Egyptian[8] and Mesopotamian thought the world was portrayed as a flat disk floating in the ocean. A similar model is found in the Homeric account of the 8th century BCE in which "Okeanos, the personified body of water surrounding the circular surface of the earth, is the begetter of all life and possibly all the gods,"[9] which forms the premise for early Greek maps such as those of Anaximander and Hecataeus of Miletus.

Many critics of the Hebrew Bible have said it carries forward ancient Middle Eastern cosmologies, such as in the Enuma Elish, which describe a flat earth with a solid roof, surrounded by water above and below,[10][11] as illustrated by references to the "foundations of the earth" and the "circle of the earth" in the following examples:

- "He sits enthroned above the circle of the earth, and its people are like grasshoppers. He stretches out the heavens like a canopy, and spreads them out like a tent to live in." Isaiah 40:22, see also Isaiah 44:24-28;Genesis 1:10,16-18; Psalms 136:7-9; Proverbs 8:27; Luke 4:5.[12]

- "For the foundations of the earth are the LORD's; upon them he has set the world." 1 Samuel 2:8; see also Job 38:4-6; Psalm 93:1

Dr. Donald DeYoung refutes this common claim with the following:

This false idea is not taught in Scripture. In the Old Testament, Job 26:7 explains that the earth is suspended in space, the obvious comparision being with the spherical sun and moon.....Bible critics have claimed that Revelation 7:1 assumes a flat earth since the verse refers to angels standing at the "four corners" of the earth. Actually, the reference is to the cardinal directions: north, south, east, and west....Bible writers used the "language of appearance" just as people always have. Without it, the intended message would be awkward at best and probably not understood at all.-from Astronomy and the Bible, Donald B. DeYoung (emphasis added)[13]

Ancient India

In antiquity, a cosmological view prevailed in India that held the Earth is a disc that consists of four continents grouped around the central mountain Meru like the petals of a flower. An outer ocean surrounds these continents.[14] This view was elaborated in traditional Jain cosmology and Buddhist cosmology, which depicts the world (in this case solar system/universe and not earth) as a vast, flat oceanic disk (of the magnitude of a small planetary system), bounded by mountains, in which the continents are set as small islands.[14] The belief in a disk remained the dominant one in Indian cosmology until the early centuries AD, such as in the Puranas:

In the Puranas the earth is a flat-bottomed, circular disk, in the center of which is a lofty mountain, Meru.[14]

Ancient China

In ancient China, the prevailing belief was that the earth was flat and square, while the heavens were round,[15] an assumption virtually unquestioned until the introduction of European astronomy in the 17th century.[16][17][18] The English sinologist Cullen emphasizes the point that there was no concept of a round earth in ancient Chinese astronomy:

Chinese thought on the form of the earth remained almost unchanged from early times until the first contacts with modern science through the medium of Jesuit missionaries in the seventeenth century. While the heavens were variously described as being like an umbrella covering the earth (the Kai Tian theory), or like a sphere surrounding it (the Hun Tian theory), or as being without substance while the heavenly bodies float freely (the Hsüan yeh theory), the earth was at all times flat, although perhaps bulging up slightly.[19]

Counterexamples by the historian Joseph Needham supposed to demonstrate dissenting voices from the general consensus actually refer without exception to the Earth's being square, not to its being flat.[20] This is also true of Zhang Heng's often quoted theory (78-139 AD) that the universe was in the oval shape of a hen's egg, and the earth itself was like the curved yolk within:

In a passage of Zhang Heng's cosmogony not translated by Needham, Zhang himself says: "Heaven takes its body from the Yang, so it is round and in motion. Earth takes its body from the Yin, so it is flat and quiescent". The point of the egg analogy is simply to stress that the earth is completely enclosed by heaven, rather than merely covered from above as the Kai Tian describes. Chinese astronomers, many of them brilliant men by any standards, continued to think in flat-earth terms until the seventeenth century; this surprising fact might be the starting-point for a re-examination of the apparent facility with which the idea of a spherical earth found acceptance in fifth-century B.C. Greece.[21]

Likewise, the 13th century scholar Li Ye, arguing that the movements of the round heaven would be hindered by a square earth,[15] did not advocate a spherical earth, but rather that its edge should be rounded off so as to be circular.[22]

Adoption of the Spherical Earth model

Classical world

- "Thales believed the Earth to be a flat disk floating on an infinite ocean ... " [13]

Many pre-Socratic philosophers considered the world to be flat, at least according to Aristotle.[24] According to Aristotle, pre-Socratic philosophers, including Leucippus (c. 440 BC) and Democritus (c. 460–370 BC) believed in a flat earth.[25] Anaximander (c. 550 BC) believed the Earth to be a short cylinder with a flat, circular top that remained stable because it is the same distance from all things.[26] It has been suggested that seafarers probably provided the first observational evidence that the Earth was not flat.[27]

Some ancient authorities in the doxographic tradition credited the Greek philosophers Pythagoras, in the 6th century BC, and Parmenides, in the 5th, with recognizing that the Earth is spherical.[28]

Around 330 BC, Aristotle provided observational evidence for the spherical Earth,[29] noting that travelers going south see southern constellations rise higher above the horizon. He argued that this was only possible if their horizon was at an angle to northerners' horizon and that the Earth's surface therefore could not be flat.[30] He also noted that the border of the shadow of Earth on the Moon during the partial phase of a lunar eclipse is always circular, no matter how high the Moon is over the horizon. Only a sphere casts a circular shadow in every direction, whereas a circular disk casts an elliptical shadow in all directions apart from directly above and directly below.[31] Writing around 10 BC, the Greek geographer Strabo cited various phenomena observed at sea as suggesting that the Earth was spherical.

He observed that elevated lights or areas of land were visible to sailors at greater distances than those less elevated, and stated that the curvature of the sea was obviously responsible for this.[32] He also remarked that observers can see further when their eyes are elevated, and cited a line from the Odyssey[33] as indicating that the poet Homer was already aware of this as early as the 7th or 8th century BC.

The Earth's circumference was first determined around 240 BC by Eratosthenes. Eratosthenes knew that in Syene, in Egypt, the Sun was directly overhead at the summer solstice, while he estimated that the angle formed by a shadow cast by the Sun at Alexandria was 1/50th of a circle. He estimated the distance from Syene to Alexandria as 5,000 stades, and estimated the Earth's circumference was 250,000 stades and a degree was 700 stades (implying a circumference of 252,000 stades).[34] Eratosthenes used rough estimates and round numbers, but depending on the length of the stadion, his result is within a margin of between 2% and 20% of the actual meridional circumference, 40,008 kilometres (24,860 mi). Note that Eratosthenes could only measure the circumference of the Earth by assuming that the distance to the Sun is so great that the rays of sunlight are essentially parallel.

In the 2nd century BC, Crates of Mallus devised a terrestrial sphere which divided the earth into four continents, separated by great rivers or oceans, with people presumed to be living in each of the four regions.[35]

Lucretius (1st. c. BC) opposed the concept of a spherical Earth, because he considered that in an infinite universe there was no center towards which heavy bodies would tend, thus he considered the idea of animals walking around topsy-turvy under the Earth to be absurd.[36][37] But by the 1st century AD, Pliny the Elder was in a position to claim that everyone agrees on the spherical shape of Earth,[38] although there continued to be disputes regarding the nature of the antipodes, and how it is possible to keep the ocean in a curved shape. Pliny also considers the possibility of an imperfect sphere, "shaped like a pinecone".[38]

In the 2nd century the Alexandrian astronomer Ptolemy advanced many arguments for the sphericity of the Earth. Among them was the observation that when sailing towards mountains, they seem to rise from the sea, indicating that they were hidden by the curved surface of the sea. He also gives separate arguments that the Earth is curved north-south and that it is curved east-west.[39] Ptolemy derived his maps from a curved globe and developed the system of latitude, longitude, and climes. His writings remained the basis of European astronomy throughout the Middle Ages, although Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages (ca. 3rd to 7th centuries) saw occasional arguments in favor of a flat Earth.

The Jerusalem Talmud says that Alexander of Macedon (Alexander the Great) was lifted by birds to the point that he saw the curvature of the Earth. This story is mentioned as well by the Tosafos commentary on the Babylonian Talmud. This is used to explain why a statue of a person holding a sphere in his hand is assumed to be an idol. The sphere being held in its hand symbolizing the idol's purported dominion over the world whose shape is a sphere.

In late antiquity such widely read encyclopedists as Macrobius (4th c.) and Martianus Capella (5th c.) discussed the circumference of the sphere of the Earth, its central position in the universe, the difference of the seasons in northern and southern hemispheres, and many other geographical details.[40] In his commentary on Cicero's Dream of Scipio, Macrobius described the Earth as a globe of insignificant size in comparison to the remainder of the cosmos.[40]

Early Christian Church

From Late Antiquity, and from the beginnings of Christian theology, knowledge of the sphericity of the Earth had become widespread.[41] There was some debate concerning the possibility of the inhabitants of the antipodes: people imagined as separated by an impassable torrid clime were difficult to reconcile with the Christian view of a unified human race descended from one couple and redeemed by a single Christ.

Saint Augustine (354–430) argued against assuming people inhabited the antipodes:

But as to the fable that there are Antipodes, that is to say, men on the opposite side of the earth, where the sun rises when it sets to us, men who walk with their feet opposite ours that is on no ground credible. And, indeed, it is not affirmed that this has been learned by historical knowledge, but by scientific conjecture, on the ground that the earth is suspended within the concavity of the sky, and that it has as much room on the one side of it as on the other: hence they say that the part that is beneath must also be inhabited. But they do not remark that, although it be supposed or scientifically demonstrated that the world is of a round and spherical form, yet it does not follow that the other side of the earth is bare of water; nor even, though it be bare, does it immediately follow that it is peopled.[42]

Since these people would have to be descended from Adam, they would have had to travel to the other side of the Earth at some point; Augustine continues:

It is too absurd to say, that some men might have taken ship and traversed the whole wide ocean, and crossed from this side of the world to the other, and that thus even the inhabitants of that distant region are descended from that one first man.

Scholars of Augustine's work have traditionally understood him to have shared the common view of his educated contemporaries that the earth is spherical, in line with the quotation above, and with Augustine's famous endorsement of science in De Genesi ad litteram.[43] That tradition has, however, recently been challenged by Leo Ferrari, who concluded that many of Augustine's passing references to the physical universe imply a belief in an essentially flat earth "at the bottom of the universe".[44][45]

Some authors and artists less prominent in the Church's history directly opposed the round Earth. After his conversion to Christianity, Lactantius (245–325) became a trenchant critic of all pagan philosophy. In Book III of The Divine Institutes[46] he ridicules the notion that there could be inhabitants of the antipodes "whose footsteps are higher than their heads". After presenting some arguments which he attributes to advocates for a spherical heaven and earth, he writes:

But if you inquire from those who defend these marvellous fictions, why all things do not fall into that lower part of the heaven, they reply that such is the nature of things, that heavy bodies are borne to the middle, and that they are all joined together towards the middle, as we see spokes in a wheel; but that the bodies that are light, as mist, smoke, and fire, are borne away from the middle, so as to seek the heaven. I am at a loss what to say respecting those who, when they have once erred, consistently persevere in their folly, and defend one vain thing by another;

Diodorus of Tarsus (d. 394) may have argued for a flat Earth based on scriptures; however, Diodorus' opinion on the matter is known to us only by a criticism of it by Photius.[47] Severian, Bishop of Gabala (d. 408), wrote that the earth is flat and the sun does not pass under it in the night, but "travels through the northern parts as if hidden by a wall".[48] The Egyptian monk Cosmas Indicopleustes (547) in his Topographia Christiana, where the Covenant Ark was meant to represent the whole universe, argued on theological grounds that the Earth was flat, a parallelogram enclosed by four oceans.

In his Homilies Concerning the Statutes[49] St.John Chrysostom (344–408) explicitly espoused the idea, based on his reading of Scripture, that the Earth floated on the waters gathered below the firmament, and St. Athanasius (c.293–373) expressed similar views in Against the Heathen.[50]

A very recent essay by Leone Montagnini, discussing the question of the shape of the Earth from the origins to the late Antiquity, has shown that the Fathers of the Church shared different approaches that paralleled their overall philosophical and theological visions. Those of them who were more close to Platonic visions, like Origen, shared peacefully the geosphericism. A second tradition, including Basil, Ambrose and Augustine, but also Philoponus, accepted the idea of the round Earth and the radial gravity, but in a critical way. In particular they pointed out a number of doubts about the physical reasons of the radial gravity, and hesitated in accepting the physical reasons proposed by Aristotles or Stoicism. However, a "flattist" approach was more or less shared by all the Fathers coming from the Syriac area, who were more inclined to follow the letter of the Old Testament. Diodorus, Severian, and Cosmas Indicopleustes, but also Chrysostom, belonged just to this latter tradition.[51]

At least one early Christian writer, Basil of Caesarea (329–379), believed the matter to be theologically irrelevant.[52]

Early Middle Ages

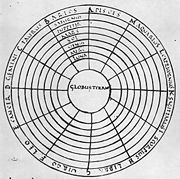

With the end of Roman civilization, Western Europe entered the Middle Ages with great difficulties that affected the continent's intellectual production. Most scientific treatises of classical antiquity (in Greek) were unavailable, leaving only simplified summaries and compilations. Still, the dominant textbooks of the Early Middle Ages supported the sphericity of the Earth. For example: many early medieval manuscripts of Macrobius include maps of the Earth, including the antipodes, zonal maps showing the Ptolemaic climates derived from the concept of a spherical Earth and a diagram showing the Earth (labeled as globus terrae, the sphere of the Earth) at the center of the hierarchically ordered planetary spheres.[53] Further examples of such medieval diagrams can be found in medieval manuscripts of the Dream of Scipio. In the Carolingian era, scholars discussed Macrobius's view of the antipodes. One of them, the Irish monk Dungal, asserted that the tropical gap between our habitable region and the other habitable region to the south was smaller than Macrobius had believed.[54]

Europe's view of the shape of the Earth in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages may be best expressed by the writings of early Christian scholars:

- Boethius (c. 480 – 524), who also wrote a theological treatise On the Trinity, repeated the Macrobian model of the Earth as an insignificant point in the center of a spherical cosmos in his influential, and widely translated, Consolation of Philosophy.[55]

- Bishop Isidore of Seville (560 – 636) taught in his widely read encyclopedia, the Etymologies, that the Earth was round and "resembles a wheel".[56] Resembling Anaximander in language and the map that he provided, this was widely interpreted as referring to a flat disc-shaped Earth[57] though some recent writers believe that he considered the Earth to be globular.[58] He did not admit the possibility of antipodes, which he took to mean people dwelling on the opposite side of the Earth[59], considering them to be legendary[60] and noting that there was no evidence for their existence.[61] Isidore's disc-shaped map continued to be used through the Middle Ages by authors, e.g. the 9th century bishop Rabanus Maurus who compared the habitable part of the northern hemisphere (Aristotle's northern temperate clime) with a wheel.

- The monk Bede (c.672 – 735) wrote in his influential treatise on computus, The Reckoning of Time, that the Earth was round, explaining the unequal length of daylight from "the roundness of the Earth, for not without reason is it called 'the orb of the world' on the pages of Holy Scripture and of ordinary literature. It is, in fact, set like a sphere in the middle of the whole universe." (De temporum ratione, 32). The large number of surviving manuscripts of The Reckoning of Time, copied to meet the Carolingian requirement that all priests should study the computus, indicates that many, if not most, priests were exposed to the idea of the sphericity of the Earth.[62] Ælfric of Eynsham paraphrased Bede into Old English, saying "Now the Earth's roundness and the Sun's orbit constitute the obstacle to the day's being equally long in every land."[63]

- Bishop Vergilius of Salzburg (c.700 – 784) was accused by St Boniface for teaching "a perverse and sinful doctrine ... against God and his own soul regarding the sphericity of the earth". Pope Zachary decided that "if it shall be clearly established that he professes belief in another world and other people existing beneath the earth, or in another sun and moon there, thou art to hold a council, and deprive him of his sacerdotal rank, and expel him from the church."[64] The issue as resolved was not the sphericity of the Earth itself, but his apparent belief that there were people living in the antipodes.[65] This raised the theological implication that these were not descended from Adam and hence were not in need of redemption. Vergilius succeeded in freeing himself from that charge; he later became a bishop and was canonised in the 13th century.[66]

A non-literary but graphic indication that people in the Middle Ages believed that the Earth (or perhaps the world) was a sphere, is the use of the orb (globus cruciger) in the regalia of many kingdoms and of the Holy Roman Empire. It is attested from the time of the Christian late-Roman emperor Theodosius II (423) throughout the Middle Ages; the Reichsapfel was used in 1191 at the coronation of emperor Henry VI. However there is no record of a globe as a representation of the earth since ancient times till that of Martin Behaim in 1492.

A recent study of medieval concepts of the sphericity of the Earth noted that "since the eighth century, no cosmographer worthy of note has called into question the sphericity of the Earth."[67] However, the work of these intellectuals may not have had significant influence on public opinion, and it is difficult to tell what the wider population may have thought of the shape of the Earth, if they considered the question at all.

High and Late Middle Ages

By the 11th century Europe had learned of Islamic astronomy. The Renaissance of the 12th century from about 1070 started an intellectual revitalization of Europe with strong philosophical and scientific roots, and increased interest in natural philosophy.

Hermannus Contractus (1013–1054) was among the earliest Christian scholars to estimate the circumference of Earth with Eratosthenes' method. Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), the most important and widely taught theologian of the Middle Ages, believed in a spherical Earth; and he even took for granted his readers also knew the Earth is round.[nb 1] Lectures in the medieval universities commonly advanced evidence in favor of the idea that the Earth was a sphere.[68] Also, "On the Sphere of the World", the most influential astronomy textbook of the 13th century and required reading by students in all Western European universities, described the world as a sphere. Thomas Aquinas, in his Summa Theologica, wrote, "The physicist proves the earth to be round by one means, the astronomer by another: for the latter proves this by means of mathematics, e.g. by the shapes of eclipses, or something of the sort; while the former proves it by means of physics, e.g. by the movement of heavy bodies towards the center, and so forth."[69]

The shape of the Earth was not only discussed in scholarly works written in Latin; it was also treated in works written in vernacular languages or dialects and intended for wider audiences. The Norwegian book Konungs Skuggsjá, from around 1250, states clearly that the Earth is round - and that it is night on the other side of the Earth when it is daytime in Norway. The author also discusses the existence of antipodes - and he notes that they (if they exist) will see the Sun in the north of the middle of the day, and that they will have opposite seasons of the people living in the Northern Hemisphere.

However Tattersall shows that in many vernacular works in 12th and 13th century French texts the earth was considered "round like a table" rather than "round like an apple". "In virtually all the examples quoted...from epics and from non-'historical' romances (that is, works of a less learned character) the actual form of words used suggests strongly a circle rather than a sphere.[70]

Dante's Divine Comedy, written in Italian in the early 14th century, portrays Earth as a sphere, discussing implications such as the different stars visible in the southern hemisphere, the altered position of the sun, and the various timezones of the Earth. Also, the Elucidarium of Honorius Augustodunensis (c. 1120), an important manual for the instruction of lesser clergy, which was translated into Middle English, Old French, Middle High German, Old Russian, Middle Dutch, Old Norse, Icelandic, Spanish, and several Italian dialects, explicitly refers to a spherical Earth. Likewise, the fact that Bertold von Regensburg (mid-13th century) used the spherical Earth as a sermonic illustration shows that he could assume this knowledge among his congregation. The sermon was held in the vernacular German, and thus was not intended for a learned audience.

Reinhard Krüger, a professor for Romance literature at the University of Stuttgart (Germany), has compiled a list of more than 100 medieval Latin and vernacular writers from the late antiquity to the 15th century—79 known by name—whom he identified as knowing that the earth was spherical.[71]

| Krüger's list can be seen by clicking on "show". |

|---|

Brunetto Latini, Visigoth king Sisebut, King Alfred of the Anglo-Saxons, Alfonso X of Castile

Basil of Caesarea, Ambrose of Milan, Aurelius Augustinus, Paulus Orosius, Jordanes, Cassiodorus, Isidore of Seville, Beda Venerabilis, Theodulf of Orléans, Vergilius of Salzburg, Irish monk Dicuil, Rabanus Maurus, Remigius of Auxerre, Johannes Scotus Eriugena, Leo of Naples (German), Gerbert d’Aurillac (Pope Sylvester II), Notker the German of Sankt-Gallen, Hermann the lame, Hildegard von Bingen, Petrus Abaelardus, Honorius Augustodunensis, Gautier de Metz, Adam of Bremen, Albertus Magnus, Thomas Aquinas, Berthold of Regensburg, Meister Eckhart, Enea Silvio Piccolomini (Pope Pius II)

Ampelius, Chalcidius, Macrobius, Martianus Capella, Boethius, Guillaume de Conches, Philippe de Thaon (French), Abu-Idrisi, Bernardus Silvestris, Petrus Comestor, Thierry de Chartres, Gautier de Châtillon, Alexander Neckam, Alain de Lille, Averroes, Moshe ben Maimon, Lambert de Saint-Omer (German), Gervasius of Tilbury, Robert Grosseteste, Johannes de Sacrobosco, Thomas de Cantimpré, Peire de Corbian, Vincent de Beauvais, Robertus Anglicus, Juan Gil de Zámora (Spanish), Perot de Garbelei (German) (divisiones mundi), Roger Bacon, Ristoro d'Arezzo, Cecco d'Ascoli, Fazio degli Uberti (Italian), Levi ben Gershon, Konrad of Megenberg, Nicole Oresme, Petrus Aliacensis, Alfonso de la Torre (German), Toscanelli

Snorri Sturluson, Marco Polo, Dante Alighieri, Brochard the German (German), Jean de Meung, Jean de Mandeville, Christine de Pizan, Geoffrey Chaucer, William Caxton, Martin Behaim, Christopher Columbus |

Portuguese exploration of Africa and Asia, Columbus voyage to the Americas (1492) and finally Ferdinand Magellan's circumnavigation of the earth (1519–21) provided the final, practical proofs for the global shape of the earth.

Ancient India

The idea of a spherical earth surrounded by the spheres of planets was finally introduced into India during the early centuries AD through the reception of Greek astronomy.[14][72] Key parts of traditional Indian astronomy, heavily attacked by progressive Indian astronomers, were discarded, while others were attempted to be adapted to the new paradigm.[14] Thus, the circumference of the Indian disk of the earth was modelled into the equator of the Greeks.[14]

The works of the classical Indian astronomer and mathematician, Aryabhata (476-550 AD), deal with the sphericity of the Earth and the motion of the planets. The final two parts of his Sanskrit magnum opus the Aryabhatiya, which were named the Kalakriya ("reckoning of time") and the Gola ("sphere"), state that the earth is spherical and that its circumference is 4,967 yojanas, which in modern units is 39,968 km (24,835 mi), which is close to the current equatorial value of 40,075 km (24,901 mi).[73][74]

Islamic world

The two main sources from which Muslim scholars drew until the introduction of modern European science in the 19th century were Aristotle's De caelo and Ptolemy's Almagest.[75] Specifically, they adopted from Greek astronomy the ideas that the earth was spherical (Spherical Earth) and at the center of the universe (Geocentric model), that the universe was without void spaces and mainly divided into the wider planetary space composed of the Four Elements on the one hand, and the celestial space beginning from the moon and extending to the edge of the universe on the other.[75]

Around 830 AD, Caliph al-Ma'mun commissioned a group of astronomers to measure the distance from Tadmur (Palmyra) to al-Raqqah, in modern Syria. They found the cities to be separated by one degree of latitude and the distance between them to be 66⅔ Arabic miles (131 km) and thus calculated the Earth's circumference to be 24000 Arabic miles (47,000 km), which differs from modern estimates by about 18.6%.[76][77]

Another estimate given by al-Ma'mun's astronomers was 56⅔ Arabic miles per degree, which corresponds to 112 kilometres (70 mi) per degree and a circumference of 40,300 km (25,000 mi), very close to the currently modern values of 111.3 km (69.2 mi) per degree and 40,068 km (24,897 mi) circumference, respectively.[78]

Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī (973-1048) solved a complex geodesic equation to accurately compute the Earth's circumference, which was close to modern values of the Earth's circumference.[79] His estimate of 6,339.9 kilometres (3,939.4 mi) for the Earth radius was only 16.8 km (10.4 mi) less than the modern value of 6,356.7 km (3,949.9 mi). In contrast to his predecessors who measured the Earth's circumference by sighting the Sun simultaneously from two different locations, al-Biruni developed a new method that used trigonometric calculations based on the angle between a plain and mountain top. This yielded more accurate measurements of the Earth's circumference, and made it possible for a single person to measured it from a single location.[80][81][82] Biruni's method was intended to avoid "walking across hot, dusty deserts" and the idea came to him when he was on top of a tall mountain in India.[82] From the top of the mountain, he sighted the dip angle which, along with the mountain's height (which he calculated beforehand), he applied to the law of sines formula.[81][82] He also made use of algebra to formulate trigonometric equations and used the astrolabe to measure angles.[83]

John J. O'Connor and Edmund F. Robertson write in the MacTutor History of Mathematics archive:

"Important contributions to geodesy and geography were also made by Biruni. He introduced techniques to measure the earth and distances on it using triangulation. He found the radius of the earth to be 6,339.6 kilometres (3,939.2 mi), a value not obtained in the West until the 16th century. His Masudic canon contains a table giving the coordinates of six hundred places, almost all of which he had direct knowledge."[84]

Muslim scholars who held to the round earth theory used it in an impeccably Islamic manner, to calculate the distance and direction from any given point on the earth to Makkah (Mecca). This determined the Qibla, or Muslim direction of prayer. Muslim mathematicians developed spherical trigonometry, which they used in these calculations.[85] Ibn Khaldun (d. 1406), in his Muqaddimah, also identified the world as spherical. The belief of some later Muslim scholars, like Suyuti (d. 1505), that the earth is flat represents a deviation from this earlier opinion.[86]

Ming China

As late as 1595, the first Jesuit missionary to China, Matteo Ricci, recorded that the Chinese say: "The earth is flat and square, and the sky is a round canopy; they did not succeed in conceiving the possibility of the antipodes".[22][87] The universal belief in a flat earth is confirmed by a contemporary Chinese encyclopedia from 1609 illustrating a flat earth extending over the horizontal diametral plane of a spherical heaven.[22]

In the 17th century, the idea of a spherical earth spread in China due to the influence of the Jesuits, who held high positions as astronomers at the imperial court. The Ge Chi Cao treatise of Xiong Ming-yu (1648) showed a printed picture of the earth as a spherical globe, with the text stating that "the round earth certainly has no square corners".[88] The text also pointed out that sailing ships could return to their port of origin after circumnavigating the waters of the earth.[88]

The influence of the map is distinctly Western, as traditional maps of Chinese cartography held the graduation of the sphere at 365.25 degrees, while the Western graduation was of 360 degrees. Also of interest to note is on one side of the world, there is seen towering Chinese pagodas, while on the opposite side (upside-down) there were European cathedrals.[88] Western influence of geographical knowledge was used by Xiong to enforce what he believed had already been argued by earlier Chinese astronomers. However, the French sinologist Jean-Claude Martzloff regards this as a retrospective interpretation:

European astronomy was so much judged worth consideration that numerous Chinese authors developed the idea that the Chinese of antiquity had anticipated most of the novelties presented by the missionaries as European discoveries, for example, the rotundity of the earth and the “heavenly spherical star carrier model.” Making skillful use of philology, these authors cleverly reinterpreted the greatest technical and literary works of Chinese antiquity. From this sprang a new science wholly dedicated to the demonstration of the Chinese origin of astronomy and more generally of all European science and technology.[16]

Modern period

"Myth of the Flat Earth" in modern historiography

During the 19th century, the Romantic conception of a European "Dark Age" gave much more prominence to the Flat Earth model than it ever possessed historically.

In 1945 the Historical Association listed "Columbus and the Flat Earth Conception" second of twenty in its first-published pamphlet on common errors in history.[89]

This belief is even repeated in some widely read textbooks. Previous editions of Thomas Bailey's The American Pageant stated that "The superstitious sailors [of Columbus' crew] ... grew increasingly mutinous...because they were fearful of sailing over the edge of the world"; however, no such historical account is known.[90] Actually, sailors were probably among the first to know of the curvature of Earth from everyday observations, for example seeing how mountains vanish below the horizon on sailing far from shore.

Some historians consider that the early advocates who projected flat Earth upon Christians of the Middle Ages were highly influential (19th century view typified by Andrew Dickson White); current historians (late 20th century view typified by historian and religious studies scholar Jeffrey Burton Russell)[6] have asserted that White's and other writings projecting flat Earth belief upon Christians are inaccurate, citing centuries of theological writings, and suggested the motivations for the promotion of such inaccuracies.

According to Russell,[91] the common misconception that people before the age of exploration believed that Earth was flat entered the popular imagination after Washington Irving's publication of The Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus in 1828.[92] Although some of the arguments attributed by Irving to Columbus's opponents had been recorded not long after the latter's death,[93] there is no record of their having argued that the Earth was flat, and noone before Iriving is known to have accused them of doing so. Modern historians have dismissed the claim that they did so as a fabrication of Irving's.[94][95][96][97]

It is notable that Copernicus, writing only twenty years after Columbus in 1514, dismisses the idea of a flat earth in two sentences and has to go back to the early Greeks to find a supporter.[98] In reality, the issue in the 1490s was not the shape but the size of the Earth, as well as the position of the east coast of Asia.

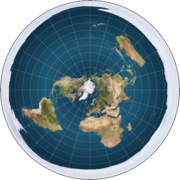

Modern flat-earthers

In the modern era, belief in a flat earth has been expressed by isolated individuals and groups, but no scientists of note.

English writer Samuel Rowbotham (1816–1885), writing under the pseudonym "Parallax," produced a pamphlet called Zetetic Astronomy in 1849 arguing for a flat earth and published results of many experiments that tested the curvatures of water over a long drainage ditch, followed by another called The inconsistency of Modern Astronomy and its Opposition to the Scripture. One of his supporters, John Hampden, lost a bet to Alfred Russell Wallace in the famous Bedford Level Experiment, which attempted to prove it. Rowbotham also produced studies that purported to show the effects of ships disappearing below the horizon could be explained by the laws of perspective in relation to the human eye.[99]

In 1883 he founded Zetetic Societies in England and New York, to which he shipped a thousand copies of Zetetic Astronomy. Challenges were issued in the New York Daily Graphic offering $10,000 to charity to anyone proving the earth revolved on axes.

William Carpenter, a printer originally from Greenwich, England, was a supporter of Rowbotham and published Theoretical Astronomy Examined and Exposed - Proving the Earth not a Globe in eight parts from 1864 under the name Common Sense. He later emigrated to Baltimore where he published A hundred proofs the Earth is not a Globe in 1885.[100] He argues that:

- "There are rivers that flow for hundreds of miles towards the level of the sea without falling more than a few feet — notably, the Nile, which, in a thousand miles, falls but a foot. A level expanse of this extent is quite incompatible with the idea of the Earth's convexity. It is, therefore, a reasonable proof that Earth is not a globe."

- "If the Earth were a globe, a small model globe would be the very best - because the truest - thing for the navigator to take to sea with him. But such a thing as that is not known: with such a toy as a guide, the mariner would wreck his ship, of a certainty!, This is a proof that Earth is not a globe."

John Jasper, the black ex-slave preacher said to have preached to more people than any Southern clergyman of his generation, echoed his friend Carpenter's sentiments in his most famous sermon "Der Sun do move and the Earth Am Square", preached over 250 times always by invitation.[101]

In Brockport, N.Y, in 1887, M.C. Flanders argued the case a flat earth for three nights against two scientific gentleman defending sphericity. Five townsmen chosen as judges voted unanimously for a flat earth at the end. The case was reported in the Brockport Democrat.[102]

Prof' Joe Holden of Maine, a former justice of the peace, gave numerous lectures in New England and lectured on flat earth theory at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago. His fame stretched to North Carolina where the Statesville Semi-weekly Landmark recorded at his death in 1900: 'We hold to the doctrine that the earth is flat ourselves and we regret exceedingly to learn that one of our members is dead'.

After Rowbotham's death, Lady Elizabeth Blount created the Universal Zetetic Society in 1893 in England and created a journal called Earth not a Globe Review, which sold for twopence, as well as one called Earth which only lasted from 1901 to 1904. She held that the Bible was the unquestionable authority on the natural world and argued that one could not be a Christian and believe the earth to be a globe. Well-known members included E. W. Bullinger of the Trinitarian Bible Society, Edward Haughton, senior moderator in natural science in Trinity College, Dublin and an archbishop. She repeated Rowbotham's experiments, generating some interesting counter-experiments, but interest declined after the First World War.[103]

In 1898, during his solo circumnavigation of the world, Joshua Slocum encountered a group of flat-earthers in Durban. Three Boers, one of them a clergyman, presented Slocum with a pamphlet in which they set out to prove that the world was flat. Paul Kruger, President of the Transvaal Republic, advanced the same view: "You don't mean round the world, it is impossible! You mean in the world. Impossible!"[104]

Wilbur Glenn Voliva, who in 1906 took over the Christian Catholic Church, a pentecostal sect that established a utopian community at Zion, Illinois, preached flat earth doctrine from 1915 onwards and used a photograph of a twelve mile stretch of the shoreline at Lake Winnebago, Wisconsin taken three feet above the waterline to prove his point. When the airship Italia disappeared on an expedition to the North Pole in 1928 he warned the world's press that it had sailed over the edge of the world. He offered a $5,000 award for proving the earth is not flat, under his own conditions.[105] Teaching a globular earth was banned in the Zion schools and the message was transmitted on his WCBD radio station.[103]

Modern biblical literalists have swung to the other extreme over flat earth theories. For example, the Biblical Astronomer website, while supporting a geocentric model of the earth, is clear on this, although its description of the foundations shows ingenuity: "In summary, the Bible teaches that the earth is basically a sphere in shape; that there are pillars which undergird the world and which we conclude to be the crystalline rock corresponding to what we commonly call the mantle."[106]

Flat Earth Society

In 1956, Samuel Shenton set up the International Flat Earth Research Society, better known as the Flat Earth Society, as a direct descendant of the Universal Zetetic Society, just before the Soviet Union launched the first artificial satellite, Sputnik. He responded to this event "Would sailing round the Isle of Wight prove that it were spherical? It is just the same for those satellites." His primary aim was to reach children before they were convinced about a spherical earth. Despite plenty of publicity, the space race eroded Shenton's support in Britain until 1967 when he started to become famous due to the Apollo program. His postbag was full but his health suffered as his operation remained essentially a one-man show till he died in 1971.[103]

Shenton's role was taken over by one of his correspondents, Charles K. Johnson, as he retired in 1972 to the Mohave Desert, California. He incorporated the IFERS and steadily built up the membership to about 3,000. He spent years examining the studies of flat and round earth theories and proposed evidence of a conspiracy against flat-earth: "The idea of a spinning globe is only a conspiracy of error that Moses, Columbus, and FDR all fought…" His article was published in the magazine Science Digest, 1980. It goes on to state,

- "If it is a sphere, the surface of a large body of water must be curved. The Johnsons have checked the surfaces of Lake Tahoe and the Salton Sea (a shallow salt lake in southern California near the Mexican border) without detecting any curvature."[109]

The Society declined in the 1990s following a fire at its headquarters in California and the death of Charles K. Johnson in 2001.[110] It was revived as a website in 2004.

Cultural references

The notion of a flat Earth continues to be referred to in a wide range of contexts. Indirect references to the theory include the widely used idiom "the four corners of the earth". The term "flat-Earther" is often used in a derogatory sense to mean anyone who holds views so antiquated as to be ridiculous.

An early mention in literature was Ludvig Holberg's comedy Erasmus Montanus (1723). Erasmus Montanus meets considerable opposition when he claims the Earth is round, since all the peasants hold it to be flat. He is not allowed to marry his fiancée until he cries "The earth is flat as a pancake". In Rudyard Kipling's The Village that Voted the Earth was Flat, the protagonists spread the rumor that a Parish Council meeting had voted in favor of a flat Earth. The 1980 film The Gods Must Be Crazy concerns a Bushman of the Kalahari who decides to travel to "the edge of the world" to dispose of a Coca-Cola bottle that he thinks has evil powers. In Jacob M. Appel's Lessons in Platygaeanism, the main character tries to convince his nephews that the earth is flat.

Fantasy fiction is particularly rich in references to flat worlds. In C. S. Lewis' The Voyage of the Dawn Treader the fictional world of Narnia is "round like a table" (i.e., flat), not "round like a ball", and the characters sail toward the edge of this world (although, in Lewis' subsequent Narnian novel The Silver Chair, the Earth itself is accepted and written as being spherical, with Narnian king Caspian X being amazed by this fact). Terry Pratchett's Discworld novels (1983 onwards) are set on a flat, disc-shaped world that rests on the backs of four huge elephants that stand on the back of an enormous turtle. Many explorers died falling off the edge trying to prove that it's not so.

Scientific satire

In a satirical piece published 1996, Albert A. Bartlett, an emeritus Professor of Physics at the University of Colorado at Boulder, uses arithmetics to show that sustainable growth on Earth is impossible in a spherical Earth since its resources are necessarily finite. He explains that only a model of a flat earth, stretching infinitely in the two horizontal dimensions and also in the vertical downward direction, would be able to accommodate the needs of a permanently growing population and economy.

The purpose of this piece is to demonstrate the impossibility of permanent growth rather than to advocate the idea of a flat earth, given that it does not present any evidence for a flat infinite earth but rather lists a number of reasons, which make this very unlikely, making the satirical character of this essay clear:

If the “we can grow forever” people are right, then they will expect us, as scientists, to modify our science in ways that will permit perpetual growth. We will be called on to abandon the “spherical earth” concept and figure out the science of the flat earth. We can see some of the problems we will have to solve. We will be called on to explain the balance of forces that make it possible for astronauts to circle endlessly in orbit above a flat earth, and to explain why astronauts appear to be weightless. We will have to figure out why we have time zones; where do the sun, moon and stars go when they set in the west of an infinite flat earth, and during the night, how do they get back to their starting point in the east. We will have to figure out the nature of the gravitational lensing that makes an infinite flat earth appear from space to be a small circular flat disk. These and a host of other problems will face us as the “infinite earth” people gain more and more acceptance, power and authority. We need to identify these people as members of "The New Flat Earth Society" because a flat earth is the only earth that has the potential to allow the human population to grow forever.”[111]

The satiric nature of the piece is also made clear by a comparison to Bartlett's other publications, which mainly advocate the necessity of curbing population growth.[112]

See also

- Spherical Earth

- Bedford Level experiment

- Geographical distance

- Hollow earth

- Scientific mythology

- Skepticism

- Denialism

Further reading

- Fraser, Raymond (2007). When The Earth Was Flat: Remembering Leonard Cohen, Alden Nowlan, the Flat Earth Society, the King James monarchy hoax, the Montreal Story Tellers and other curious matters. Black Moss Press, ISBN 978-0-88753-439-3

- Garwood, Christine (2007) Flat Earth: The History of an Infamous Idea, Pan Books, ISBN 140504702X

- Simek, Rudolf (trans.Angela Hall) "Heaven and Earth in the Middle Ages"[14]

Notes

- ↑ When Aquinas wrote his Summa, at the very beginning (Summa Theologica Ia, q. 1, a. 1; see also Summa Theologica IIa Iae, q. 54, a. 2), the idea of a round earth was the example used when he wanted to show that fields of science are distinguished by their methods rather than their subject matter... "Sciences are distinguished by the different methods they use. For the astronomer and the physicist both may prove the same conclusion - that the earth, for instance, is round: the astronomer proves it by means of mathematics, but the physicist proves it by the nature of matter. History of Science: Shape of the Earth: Middle Ages: Aquinas"

References

- ↑ "Their cosmography as far as we know anything about it was practically of one type up til the time of the white man's arrival upon the scene. That of the Borneo Dayaks may furnish us with some idea of it. 'They consider the earth to be a flat surface, whilst the heavens are a dome, a kind of glass shade which covers the earth and comes in contact with it at the horizon.'" Lucien Levy-Bruhl, Primitive Mentality (repr. Boston: Beacon, 1966) 353; "The usual primitive conception of the world's form ... [is] flat and round below and surmounted above by a solid firmament in the shape of an inverted bowl." H. B. Alexander, The Mythology of All Races 10: North American (repr. New York: Cooper Square, 1964) 249.

- ↑ Continuation of Greek concept into Roman and medieval Christian thought: Reinhard Krüger: Materialien und Dokumente zur mittelalterlichen Erdkugeltheorie von der Spätantike bis zur Kolumbusfahrt (1492)

- ↑ Direct adoption of the Greek concept by Islam: Ragep, F. Jamil: "Astronomy", in: Krämer, Gudrun (ed.) et al.: Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE, Brill 2010, without page numbers

- ↑ Direct adoption by India: D. Pingree: "History of Mathematical Astronomy in India", Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. 15 (1978), pp. 533−633 (554f.); Glick, Thomas F., Livesey, Steven John, Wallis, Faith (eds.): "Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia", Routledge, New York 2005, ISBN0-415-96930-1, p. 463

- ↑ Adoption by China via European science: Jean-Claude Martzloff, “Space and Time in Chinese Texts of Astronomy and of Mathematical Astronomy in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries”, Chinese Science 11 (1993-94): 66-92 (69) and Christopher Cullen, "A Chinese Eratosthenes of the Flat Earth: A Study of a Fragment of Cosmology in Huai Nan tzu 淮 南 子", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Vol. 39, No. 1 (1976), pp. 106-127 (107)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Russell, Jeffrey B.. "The Myth of the Flat Earth". American Scientific Affiliation. http://www.asa3.org/ASA/topics/history/1997Russell.html. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

- ↑ Members of the Historical Association (1945). Common errors in history. General Series, G.1. London: P.S. King & Staples for the Historical Association., pp.4–5. The Historical Association published a second list of 17 other common errors in 1947.

- ↑ H. and H. A. Frankfort, J. A. Wilson, and T. Jacobsen, Before Philosophy (Baltimore: Penguin, 1949) 54.

- ↑ Anthony Gottlieb (2000). The Dream of Reason. Penguin. p. 6.

- ↑ Seeley The Geographical Meaning of "Ëarth" and "Seas" in Genesis 1:10, Westminster Theological Journal 59 (1997), p.246

- ↑ Paul H. Seely, The Firmament and the Water Above, Westminster Theological Journal 53 (1991)

- ↑ For biblical quotations see

- ↑ DeYoung, Donald; "Astronomy and the Bible, Questions and Answers"; pp. 17; ISBN 0-8010-6225-X

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 D. Pingree: "History of Mathematical Astronomy in India", Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. 15 (1978), pp. 533−633 (554f.)

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd. pp. 498.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Jean-Claude Martzloff, “Space and Time in Chinese Texts of Astronomy and of Mathematical Astronomy in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries”, Chinese Science 11 (1993-94): 66-92 (69)" (PDF). http://www.uni-tuebingen.de/uni/ans/eastm/back/cs11/cs11-4-martzloff.pdf.

- ↑ Christopher Cullen, “Joseph Needham on Chinese Astronomy”, Past and Present, No. 87. (May, 1980), pp. 39-53 (42 & 49)

- ↑ Christopher Cullen, "A Chinese Eratosthenes of the Flat Earth: A Study of a Fragment of Cosmology in Huai Nan tzu 淮 南 子", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Vol. 39, No. 1 (1976), pp. 106-127 (107-109)

- ↑ Christopher Cullen, "A Chinese Eratosthenes of the Flat Earth: A Study of a Fragment of Cosmology in Huai Nan tzu 淮 南 子", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Vol. 39, No. 1 (1976), pp. 106-127 (107)

- ↑ Christopher Cullen, "A Chinese Eratosthenes of the Flat Earth: A Study of a Fragment of Cosmology in Huai Nan tzu 淮 南 子", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Vol. 39, No. 1 (1976), pp. 106-127 (108)

- ↑ Christopher Cullen, “Joseph Needham on Chinese Astronomy”, Past and Present, No. 87. (May, 1980), pp. 39-53 (42)

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Christopher Cullen, "A Chinese Eratosthenes of the Flat Earth: A Study of a Fragment of Cosmology in Huai Nan tzu 淮 南 子", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Vol. 39, No. 1 (1976), pp. 106-127 (109)

- ↑ According to John Mansley Robinson, An Introduction to Early Greek Philosophy, Houghton and Mifflin, 1968.

- ↑ Burch, George Bosworth (1954). "The Counter-Earth". Osirus (Saint Catherines Press) 11: 267–294. doi:10.1086/368583.

- ↑ De Fontaine, Didier (2002). "Flat worlds: Today and in antiquity". Memorie della Società Astronomica Italiana, special issue 1 (3): 257–62. http://www.mse.berkeley.edu/faculty/deFontaine/flatworlds.html. Retrieved 2007-08-03.

- ↑ Anaximander; Fairbanks (editor and translator), Arthur. "Fragments and Commentary". The Hanover Historical Texts Project. http://history.hanover.edu/texts/presoc/anaximan.htm. (Plut., Strom. 2 ; Dox. 579).

- ↑ Hugh Thurston, Early Astronomy, (New York: Springer-Verlag), p. 118. ISBN 0-387-94107-X.

- ↑ Dreyer, John Louis Emil (1953) [1905]. A History of Astronomy from Thales to Kepler. New York, NY: Dover Publications. pp. 20, 37–38. http://www.archive.org/details/historyofplaneta00dreyuoft.

- ↑ Lloyd, G.E.R. (1968). Aristotle: The Growth and Structure of His Thought. Cambridge Univ. Press. pp. 162–164.

- ↑ Aristotle, De caelo, 297b24-31

- ↑ Aristotle, De caelo, 297b31-298a10

- ↑ Strabo (1960) [1917]. The Geography of Strabo, in Eight Volumes. Loeb Classical Library edition, translated by Horace Leonard Jones, A.M., Ph.D.. London: William Heinemann., Vol.I Bk. I para. 20, pp.41, 43. An earlier edition is available online.

- ↑ Odyssey, Bk. 5 393: "As he rose on the swell he looked eagerly ahead, and could see land quite near." Samuel Butler's translation is available online.

- ↑ Van Helden, Albert (1985). Measuring the Universe: Cosmic Dimensions from Aristarchus to Halley. University of Chicago Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 0-226-84882-5.

- ↑ Stevens, Wesley M. (1980). "The Figure of the Earth in Isidore's "De natura rerum"". Isis 71 (2): 268–77. http://www.jstor.org/pss/230175, page 269

- ↑ Sedley, David N. (2003), Lucretius and the Transformation of Greek Wisdom, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 78–82, ISBN 9780521542142

- ↑ Lucretius, De rerum natura, 1.1052-82.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Natural History, 2.64

- ↑ Ptolemy. Almagest. pp. I.4. as quoted in Grant, Edward (1974). A Source Book in Medieval Science. Harvard University Press. pp. 63–4.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Macrobius. Commentary on the Dream of Scipio, V.9-VI.7, XX.. pp. 18–24., translated in Stahl, W. H. (1952). Martianus Capella, The Marriage of Philology and Mercury. Columbia University Press.

- ↑ As depicted by the (spherical) globus cruciger, on coins by Theodosius II

- ↑ De Civitate Dei, Book XVI, Chapter 9 — Whether We are to Believe in the Antipodes, translated by Rev. Marcus Dods, D.D.; from the Christian Classics Ethereal Library at Calvin College

- ↑ q:Augustine of Hippo

- ↑ Leo Ferrari, Cosmography, in Augustine through the Ages: An Encyclopedia, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., Grand Rapids MI, 1999, p.246

- ↑ Leo Ferrari, Augustine's Cosmography, Augustinian Studies, 27:2 (1996), 129-177.

- ↑ Lactantius, The Divine Institutes, Book III, Chapter XXIV, THE ANTE-NICENE FATHERS, Vol VII, ed. Rev. Alexander Roberts, D.D., and James Donaldson, LL.D., American reprint of the Edinburgh edition (1979), W.B.Eerdmans Publishing Co.,Grand Rapids, MI, pp.94-95.

- ↑ J. L. E. Dreyer, A History of Planetary Systems from Thales to Kepler. (1906); unabridged republication as A History of Astronomy from Thales to Kepler (New York: Dover Publications, 1953).

- ↑ J.L.E. Dreyer, A History of Planetary Systems', (1906), p.211-12.

- ↑ St. John Chrysostom, Homilies Concerning the Statutes, Homily IX [1], paras.7-8, in A SELECT LIBRARY OF THE NICENE AND POST-NICENE FATHERS OF THE CHRISTIAN CHURCH, Series I, Vol IX, ed. Philip Schaff, D.D.,LL.D., American reprint of the Edinburgh edition (1978), W.B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.,Grand Rapids, MI, pp.403-404.

- ↑ St.Athanasius, Against the Heathen, Ch.27 [2], Ch 36 [3], in A SELECT LIBRARY OF THE NICENE AND POST-NICENE FATHERS OF THE CHRISTIAN CHURCH, Series II, Vol IV, ed. Philip Schaff, D.D.,LL.D., American reprint of the Edinburgh edition (1978), W.B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.,Grand Rapids, MI.

- ↑ See Leone Montagnini, La questione della forma della Terra. Dalle origini alla tarda Antichità, in Studi sull'Oriente Cristiano, 13/II: 31-68

- ↑ Saint Basil the Great, Hexaemeron 9 - HOMILY IX - "The creation of terrestrial animals" Holy Inocents Orthodox Church.[4]

- ↑ B. Eastwood and G. Graßhoff, Planetary Diagrams for Roman Astronomy in Medieval Europe, ca. 800-1500, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, 94, 3 (Philadelphia, 2004), pp. 49-50.

- ↑ Bruce S. Eastwood, Ordering the Heavens: Roman Astronomy and Cosmology in the Carolingian Renaissance, (Leiden: Brill, 2007), pp. 62-3.

- ↑ S. C. McCluskey, Astronomies and Cultures in Early Medieval Europe, (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1998), pp. 114, 123.

- ↑ Stephen A. Barney, W. J. Lewis, J. A. Beach, Oliver Berghof (translators) (2010). "XIV ii 1". The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521837491. http://books.google.com/?id=3ep502syZv8C&printsec=frontcover.

- ↑ Lyons, Jonathan (2009). The House of Wisdom. Bloomsbury. pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Wesley M. Stevens, "The Figure of the Earth in Isidore's De natura rerum", Isis, 71(1980): 268-277.

- ↑ Stevens, Wesley M. (1980). "The Figure of the Earth in Isidore's "De natura rerum"". Isis 71 (2): 268–77. http://www.jstor.org/pss/230175, page 274

- ↑ Isidore, Etymologiae, XIV.v.17 [5].

- ↑ Isidore, Etymologiae, IX.ii.133 [6].

- ↑ Faith Wallis, trans., Bede: The Reckoning of Time, (Liverpool: Liverpool Univ. Pr., 2004), pp. lxxxv-lxxxix.

- ↑ Ælfric of Eynsham, On the Seasons of the Year, Peter Baker, trans

- ↑ MGH, Epistolae Selectae 1, 80, pp. 178-9.[7]; translation in M. L. W. Laistner, Thought and Letters in Western Europe: A.D. 500 to 900, 2nd. ed., (Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Pr., 1955), pp. 184-5.

- ↑ Carey, John (1989). "Ireland and the Antipodes: The Heterodoxy of Virgil of Salzburg". Speculum 64 (1): 1–10. doi:10.2307/2852184. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2852184

- ↑ Catholic Encyclopedia

- ↑ Klaus Anselm Vogel, "Sphaera terrae - das mittelalterliche Bild der Erde und die kosmographische Revolution," PhD dissertation Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, 1995, p. 19.[8]

- ↑ E. Grant, Planets. Stars, & Orbs: The Medieval Cosmos, 1200-1687, (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1994), pp. 626-630.

- ↑ "Summa Theologica IIa Iae, q. 54, a. 2". http://www.newadvent.org/summa/2054.htm#2.

- ↑ Jill Tattersall (1981). "The Earth, Sphere or Disc?". Modern Language Review 76: 31–46.

- ↑ Reinhard Krüger, Materialien und Dokumente zur mittelalterlichen Erdkugeltheorie von der Spätantike bis zur Kolumbusfahrt (1492) [9]

- ↑ Glick, Thomas F., Livesey, Steven John, Wallis, Faith (eds.): "Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia", Routledge, New York 2005, ISBN0-415-96930-1, p. 463

- ↑ "Aryabhata I biography". History.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk. November 2000. http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Aryabhata_I.html. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ↑ Gongol, William J. (December 14, 2003). "The Aryabhatiya: Foundations of Indian Mathematics". GONGOL.com. http://www.gongol.com/research/math/aryabhatiya. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 Ragep, F. Jamil: "Astronomy", in: Krämer, Gudrun (ed.) et al.: Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE, Brill 2010, without page numbers

- ↑ Gharā'ib al-funūn wa-mulah al-`uyūn (The Book of Curiosities of the Sciences and Marvels for the Eyes), 2.1 "On the mensuration of the Earth and its division into seven climes, as related by Ptolemy and others", (ff. 22b-23a)

- ↑ John Brian Harley and David Woodward (ed.), The History of cartography, Volume 2, Book 1: Cartography in the Traditional Islamic and South Asian Societies (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), p.177, ISBN 0-226-31635-1. The medieval arabic mile was 1.972 km.

- ↑ Edward S. Kennedy, Mathematical Geography, pp=187–8, in (Rashed & Morelon 1996, pp. 185–201)

- ↑ James S. Aber (2003). Al-biruni calculated the Earth's circumference at a small town of Pind Dadan Khan, District Jhelum, Punjab, Pakistan.Abu Rayhan al-Biruni, Emporia State University.

- ↑ Lenn Evan Goodman (1992), Avicenna, p. 31, Routledge, ISBN 041501929X.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 Behnaz Savizi (2007). "Applicable Problems in History of Mathematics: Practical Examples for the Classroom". Teaching Mathematics and Its Applications (Oxford University Press) 26 (1): 45–50. doi:10.1093/teamat/hrl009 (cf. Behnaz Savizi. "Applicable Problems in History of Mathematics; Practical Examples for the Classroom". University of Exeter. http://people.exeter.ac.uk/PErnest/pome19/Savizi%20-%20Applicable%20Problems.doc. Retrieved 2010-02-21.)

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 82.2 Beatrice Lumpkin (1997). Geometry Activities from Many Cultures. Walch Publishing. pp. 60 & 112–3. ISBN 0825132851 [10]

- ↑ Jim Al-Khalili, The Empire of Reason 2/6 (Science and Islam - Episode 2 of 3) at YouTube, BBC

- ↑ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Al-Biruni", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Al-Biruni.html.

- ↑ David A. King, Astronomy in the Service of Islam, (Aldershot (U.K.): Variorum), 1993.

- ↑ History, Science and Civilization: Early Muslim Consensus: The Earth is Round.

- ↑ A spherical terrestrial globe was introduced to Beijing in 1267 by the Persian astronomer Jamal ad-Din, but it is not known to have made an impact on the traditional Chinese conception of the shape of the Earth (cf. Joseph Needham et al.: "Heavenly clockwork: the great astronomical clocks of medieval China", Antiquarian Horological Society, 2nd. ed., Vol. 1, 1986, ISBN 0-521-32276-6, p. 138)

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 88.2 Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd. pp. 499.

- ↑ Members of the Historical Association (1945). Common errors in history. General Series, G.1. London: P.S. King & Staples for the Historical Association., pp.4–5. The Historical Association published a second list of 17 other common errors in 1947.

- ↑ James. W. Loewen, Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your History Textbook Got Wrong, (Touchstone Books, 1996), p. 56

- ↑ Russell, Jeffey Burton (1991), Inventing the Flat Earth—Columbus and Modern Historians, Westport, CT: Praeger, pp. 49–58, ISBN 0-275-95904-X

- ↑ Washington, Irving (1828). The Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus. pp. 117–130. http://books.google.com/?id=uIADAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA127&q.

- ↑ In the biography of Columbus, for example, written by his son, Ferdinand, shortly before the latter's death in 1539: Columbus, Ferdinand (1959) [1571]. The life of the Admiral Christopher Columbus by his son Ferdinand. Translated and annotated by Benjamin Keen. The Folio Society.

- ↑ Morison, Samuel Eliot (1942), Admiral of the Ocean Sea. A Life of Christofer Columbus, Camden, NJ: Little, Brown and Co., p. 89, http://books.google.com.au/books?id=T5x5xjsJtlwC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ Garwood, Christine (2008) [2007], Flat Earth—The History of an Infamous Idea, London: Pan Books, pp. 7–8, ISBN 978-0-330-43289-4

- ↑ Love, Ronald S. (2006), Maritime Exploration in the Age of Discovery, 1415–1800, Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, pp. 41–42, ISBN 0-313-32043-8, http://books.google.com.au/books?id=YFFmpK0t98UC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ Sale, Kirkpatrick (2006) [1991], Christopher Columbus and the Conquest of Paradise, London: Tauris Parke Paperbacks, p. 344, ISBN 1-84511-154-0, http://books.google.com.au/books?id=g9uH9kL0PoIC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ "Therefore the earth is not flat, as Empedocles and Anaximenes thought" Nicholas Copernicus (1543). On the revolutions. http://www.webexhibits.org/calendars/year-text-Copernicus.html.

- ↑ Parallax (Samuel Birley Rowbotham) (1881). Zetetic Astronomy: Earth Not a Globe (Third ed.). London:Simpkin, Marshall, and Co.. http://www.sacred-texts.com/earth/za/za32.htm.

- ↑ William Carpenter, One hundred proofs that the earth is not a globe, (Baltimore: The author, 1885).[11]

- ↑ 'Low me ter ax ef de earth is roun', whar do it keep its corners? Er flat, squar thing has corners, but tell me where is de cornur uv er appul, ur a marbul, ur a cannun ball, ur a silver dollar.' William E. Hatcher (1908). John Jasper. Fleming Revell. http://www.archive.org/stream/johnjasperunmatc00hatciala/johnjasperunmatc00hatciala_djvu.txt. See also Garwood, p165

- ↑ The Earth: Scripturally, Rationally, and Practically Described. A Geographical, Philosophical, and Educational Review, Nautical Guide, and General Student’s Manual, n. 17 (November 1, 1887), p. 7. cited in Robert J. Schadewald (1981). "Scientific Creationism, Geocentricity, and the Flat Earth". Skeptical Inquirer. http://www.lhup.edu/~dsimanek/crea-fe.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-21.

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 103.2 Christine Garwood (2007). Flat Earth. Macmillan.

- ↑ Joshua Slocum, Sailing Alone Around the World, (New York: The Century Company, 1900), chaps. 17-18.[12]

- ↑ . ModernMechanix. Oct 1931. http://blog.modernmechanix.com/2006/05/19/5000-for-proving-the-earth-is-a-globe/. Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- ↑ "Does the Bible teach a flat earth?". http://www.geocentricity.com/astronomy_of_bible/flatearth/doesbibleteach.html. Retrieved 2010-07-23.

- ↑ Schadewald, Robert J "The Flat-out Truth:Earth Orbits? Moon Landings? A Fraud! Says This Prophet" Science Digest July 1980

- ↑ Schick, Theodore; Lewis Vaughn How to think about weird things: critical thinking for a new age Houghton Mifflin (Mayfield) (31 Oct 1995) ISBN 978-1559342544 p.197

- ↑ "The Flat-out Truth". http://www.lhup.edu/~DSIMANEK/fe-scidi.htm. Retrieved 2007-09-15.

- ↑ Donad E. Simanek, The Flat Earth.

- ↑ "The New Flat Earth Society". Jclahr.com. http://jclahr.com/bartlett/flat-earth.html. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

- ↑ "Albert Bartlett On Growth". Jclahr.com. 2006-11-28. http://jclahr.com/bartlett/. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

External links

- The Myth of the Flat Earth

- The Myth of the Flat Universe

- 7000 Years of Thinking Regarding Earth's Shape

- You say the earth is round? Prove it (from The Straight Dope)

- Flat Earth Fallacy

- Zetetic Astronomy, or Earth Not a Globe by Parallax (Samuel Birley Rowbotham (1816-1884)) at sacred-texts.com

- The flat-earth myth and creationism